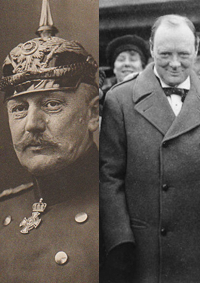

Churchill: Architect of Catastrophe, 1914

How a legendary politician needlessly took Britain into a continental war in 1914.

February 22, 2014

Germany’s errors added up to the catastrophes of World War I and much that followed. But they were not alone in faulty decision-making.

To see why, let’s switch the scene: Britain, at that moment in August 1914, was ruled by a Liberal Party government, supported by the Irish Home Rule Party. That partnership gave the Liberal Party’s coalition a strong 80-seat majority in the House of Commons, the main chamber of the British parliament.

The rank and file of Liberal Party Members of Parliament, as well as virtually all their supporters around Britain was implacably opposed to getting embroiled in a general European war. William Ewart Gladstone, the founder and spiritual guide of the Liberal Party, had always implacably opposed such a needless and insanely risky adventure.

Enter the British cabal

It was a cabal of only four men, pressuring a weak, lazy prime minister — Herbert Henry Asquith — that was entirely responsible for the fatal decision to go to war. They were:

- Foreign Secretary Edward Grey,

- Chancellor of the Exchequer (i.e. Finance Minister) David Lloyd George,

- Lord High Chancellor and Former War Minister Lord Haldane (ironically of German descent himself) and

- None other than Winston Churchill, then the civilian head of the Royal Navy, First Lord of the Admiralty.

When it came to assessing the threat from Belgium, it was Churchill’s professional assessment that carried the day. He viewed the potential fall of Belgium and its seaports to the Germans as creating a grave threat to the British homeland – one that had to be answered pre-emptively by a counter-invasion.

Churchill won high marks at the time, and has been often praised by British historians since, for his industry and energy in preparing the Royal Navy, the most powerful in the world.

For good reason, Churchill saw to it that the Royal Navy was ready for any possible war with Germany. The latter then had the world’s second-largest battleship fleet (followed by the rapidly growing United States Navy).

Churchill’s reputation was well-deserved. Yet, what was completely overlooked at the time – and ever since – was that it was Churchill’s very success in preparing the British Navy for a modern sea war that made the issue of the Belgian ports strategically irrelevant.

Years before the war, Churchill had taken a far-reaching strategic decision. For the duration of any war with Germany, he would not base the Navy at its traditional home ports in the English Channel.

Instead Britain’s navy would operate out of the remote anchorage of Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, north of Scotland. This would give Britain naval control of the North Sea and the ability to respond to German maneuvers in any direction.

His decision proved so successful and so well-founded that the British Navy followed it with equal success a quarter century later for the duration of World War II as well.

Both Germany’s home naval bases and Belgium’s ports lie on the south coast of the North Sea to the east of the English Channel.

No German surface fleet in either world war ever managed to break out of the narrow and heavily patrolled Dover Strait/English Channel to the south into the Atlantic. Therefore, any German breakout attempt would still have to pass northward between Norway and the Orkney Islands.

By basing the surface fleet at Scapa Flow, Churchill bottled up the Imperial German Navy at its home anchorages east and west of the Kiel Canal. This neutralized Germany’s ability to bring its full strength to bear and prevented Britain from being surrounded, even with access to Belgian ports.

Yet, this masterful strategy move ran directly counter to a large body of historic evidence that made Britain understandably nervous about those Belgian ports.

From Belgium to world glory?

Control of the Belgian ports had been valuable for previous European continental rulers for war with England. They were a launching pad for Philip II of Spain’s Armada in the 16th century, as well as for attacks by King Louis XIV of France in the 17th century and Napoleon Bonaparte of France at the beginning of the 19th century.

However, there was one innovation that made the Belgian ports an irrelevance in the early 20th century. This was the development of large, armored, oil-turbine–powered battleships. And those acquisitions were none other than Churchill’s very contribution to Britain’s strategic arsenal.

The Belgian ports ended up being occupied by Germany in both world wars. They proved worthless to the German Navy, in both of them.

They were no better positioned than German homeports with regard to the problematic English Channel. And for breakout routes into the North Atlantic around Scotland, they were actually farther away than Germany’s homeports for the surface fleet. Even the savings in distance they gave Germany’s underwater U-boat fleet were negligible in both world wars.

In World War I, the German U-boat campaign briefly assumed formidable dimensions in mid-1917. But became ineffective as soon as the Royal Navy, then led by First Lord of the Admiralty Eric Geddes and First Sea Lord Rosslyn Wemyss, belatedly switched to a convoy system to protect surface merchant ships.

The far greater size, range and speed of oil-fired, turbine-powered battleships and the speed and striking power of surface destroyers also made command of the Belgian ports irrelevant. Those ports only posed a unique threat to Britain in the era of sail and wind-power at sea.

Moltke was Germany’s supreme professional soldier. Churchill was the most hands-on and intrusive civilian head the Royal Navy ever had. All his Liberal government colleagues deferred to his undoubted technical expertise in matters of naval strategy and war at sea.

The best-laid plans

Yet, Moltke did not know, or forgot in his panic, one of the most important alternative plans of his own planning staff. And Churchill, for all his brilliance, never realized how the technical developments and choice of Scapa Flow as a war base, which he had personally approved, made control of the Belgian ports irrelevant for modern naval war.

The appalling mistakes that Moltke and Churchill made in 1914, and the failure of Kaiser Wilhelm in Germany and Prime Minister Asquith in Britain, to question their assumptions, have sobering lessons for 21st century Western policymakers.

JFK as a student of history

John F. Kennedy quickly learned during the Cuban Missile Crisis that he dared not trust the bellicose instincts of his own top Air Force generals. They would rather have plunged the world into nuclear war than to let a provocation go – or negotiate it away – for the sake of peace.

However, after Kennedy’s assassination, his successor Lyndon Johnson, naively plunged deep into the massive American commitment in Vietnam.

The reason was simple: A man who had focused on domestic policy for his whole career until Kennedy’s assassination lacked the confidence (or the expertise) to question his own hawkish advisers who assured him it was unavoidable.

Ironically, peaceful political leaders who have no taste for war, or professional or historical knowledge of how it is waged, are the most likely to stumble into it.

In the United States, for example, presidents who have been successful generals – men like George Washington, Andrew Jackson, Zachary Taylor, Ulysses S. Grant and Dwight D. Eisenhower — have often been the most successful at preserving the peace.

The easily avoidable mistakes of Moltke and Churchill doomed the very empires they served and ultimately cost scores of millions of innocent lives.

The Russian Revolution, the Ukrainian Holodomor genocide-famine, Stalin’s Great Terror and Hitler’s Holocaust might never have happened if Britain and Germany had not been pulled into mutually ruinous conflict in 1914.

Takeaways

Churchill was the most hands-on and intrusive civilian head the Royal Navy ever had.

Liberal government colleagues deferred to Churchill’s undoubted technical expertise in matters of naval strategy.

Ironically, peaceful leaders with little knowledge of how war is waged are the most likely to stumble into it.

Without 1914’s errors, the Russian Revolution, Stalin’s Terror and Hitler’s Holocaust might never have happened.

Read previous

Moltke: Architect of Catastrophe, 1914

February 22, 2014