Premier Li as Fitzcarraldo: China’s Latin Role

While China’s role in Latin America is growing, it is likely to remain limited.

May 29, 2015

China’s Premier Li Keqiang has just returned from his tour through Latin America. While in the region, he promised $50 billion in infrastructure investments.

His Latin American counterparts pin high hopes on a broader and stronger engagement by China on the continent. After a great first decade this century, the region on the whole is not doing well, even though there are some countries that are doing better than others.

While China’s Latin role is definitely rising, it is most likely going to remain relatively limited. This assessment may come as a surprise. After all, Latin America is highly exposed to China, for good and for bad.

After benefiting from a commodities boom, Latin America’s exporters of soybeans, crude oil, iron ore and copper have to contend with lower prices and export receipts.

In fact, the cooling of China’s economy has sparked a commodities glut. Such are the consequences of Latin American growth becoming increasingly China-centric since 2000.

However, beyond the simple mechanics of growth linkages, the impact of China’s ongoing economic re-balancing is bound to result in another hit on Latin America’s China-related prospects.

Consumption-driven China weakens Latin America

What is now the world’s largest economy, when measured in PPP terms, moves away from hard equipment investment. Many economies in Latin America that are materially reliant on commodities exports for growth will have to contend with further moderation of their growth prospects.

The reason for this is simple. A growth model that is dependent on equipment investment is also commodity-dependent (or at least biased towards the use of industrial and energy commodities, such as copper, oil and iron ore).

In contrast, a consumption-led growth model is likely to be less commodity-intensive. For this reason, a consumption-driven China tends to weaken Latin America.

Consider the case of Chile, one of the star performers of the region. In 2013, Chile’s exports to China, largely copper, totaled 7.4% of its GDP. Between early 2012 and early 2015, the price of copper dropped by half, as China’s investment-led growth started to slow down.

The corresponding income effect of lower terms of trade must have been very strong indeed. Chile’s annual income windfall over the past 40 years, almost 2% of GDP, turned into heavy losses until recently, when copper prices started to climb back up.

Chinese transport channels from Atlantic to Pacific

Even so, given that government finances are running dry, Latin American countries are trying hard to woo Chinese investment. Deep Chinese pockets are projected to cut transport channels from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans.

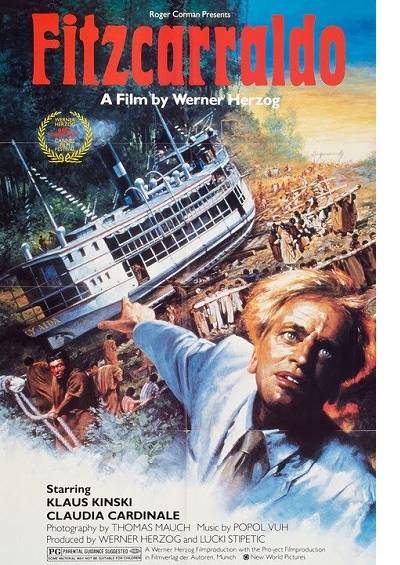

In that context, Werner Herzog’s film Fitzcarraldo comes to mind. In the film, the protagonist Fitzcarraldo (played by Klaus Kinski) moved his ship across mountains to build an opera in the tropical forest.

Undoubtedly, Latin America has considerable needs for infrastructure investments, such as a rail link from Brazil to Peru’s Pacific Coast. The business case for this investment is clear-cut. It will help lower transportation costs to support what has become a high level of Latin American-Chinese trade ($240 billion in 2014).

A Nicaragua-crossing interoceanic canal is estimated to trigger $50 billion of Chinese investment to Central America — if it comes to pass.

Trade links are becoming increasingly important, as Latin American countries are also interested in pushing manufactured and services exports (mainly tourism) to China.

China has now surpassed the United States as Brazil’s biggest trade partner. Both sides hope for better diversification and value-added enhancement.

Meanwhile, because China needs to deploy excess savings and employ excess Chinese infrastructure-building capacities, it is wooing mining concessions in Latin America.

China targeting developing countries

In a broader global context, China has indeed experienced a diplomatic transformation. It has evolved from mostly low profile to now more proactive and enterprising.

China’s “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) strategy and its 21st Century Maritime Silk Road are targeting developing countries. After initially focusing on expanding its reach in Asia and across Africa, China is now shifting focus to Latin America.

Geopolitical shifts manifest themselves most visibly via intensified travel diplomacy of top leaders. This became evident with China’s President Xi Jinping visiting Argentina, Brazil, Cuba and Venezuela in 2014. Recently, premier Li Keqiang went to Brazil (again), and also to Chile, Colombia and Peru.

Apart from travel diplomacy, there has also been summitry, including the CELAC-China ministerial early 2015 in Beijing, various BRICS summits and the announcement of various cooperation plans, such as the China-Latin American Countries Cooperation Plan (2015-2019).

China is also looking at human development and soft power aspects. It has opened up scholarships and training opportunities (6,000 in each case) for Chinese going to Latin America. For some countries (Venezuela, Ecuador, Argentina), China has assumed lender-of-last-resort functions.

However, despite big announcements and high hopes, China’s Latin role is likely to remain limited compared to Asia and Africa.

Barriers to China’s engagement

1. China is growing increasingly worried about the model of lending secured against commodities. Last year, Chinese loans to Latin America reached $22 billion, surpassing the combined lending of long-established institutions such as the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank, according to estimates from the Inter-American Dialogue.

As a result, default concerns have been creeping in. Venezuela, for instance, has borrowed more than $56 billion from the China Development Bank, but the economy has hit a slow patch due to a steep drop in crude oil prices.

Argentina’s government, facing severe dollar shortages and a protracted legal dispute with U.S. creditors, has repeatedly turned to Chinese credit to bolster depleted foreign currency reserves.

Growing concerns over its financial exposure to socialist-leaning South American partners such as Venezuela and Argentina are pushing for diversification of Chinese finance in the region.

2. LAC is traditionally part of U.S. sphere, and that will limit the scope of China-Latin America ties.

Here is a Chinese perspective on the matter:

Culturally, Latin America has been part of Western civilization. Geographically, it borders the U.S., thus the regional economies are closely tied to the United States’. Some Latin American countries rely on the U.S. for security or are deeply influenced by the U.S. Meanwhile, the U.S. considers Latin America as its “backyard” and has a great impact on, or even dominates, some Latin American countries’ domestic and foreign affairs. U.S. influence is wielded through the Organization of American States (OAS), the Inter-American Development Bank, bilateral economic cooperation and assistance, multinational corporations, military aid, and even military intervention. When it comes to Latin America and the Caribbean, U.S. tolerance for China to expand partnerships and economic interests within this region is one thing; the development of military and security ties is quite another. Conversely, China could set up security and military alliances with African states if necessary, as that continent is far less influenced by the U.S. and Europe.

Come to think of it, the recent warming of Cuba-U.S. relations must be viewed as a U.S. response to China’s advances in America’s traditional backyard.

3. Both Latin America and Africa are less important than Eurasia in China’s “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) strategy. The China-Latin America relationship is of even lesser significance than China-Africa ties, considering the factors of geographical distance, the United States’ influence, weak economic ties, cultural differences and a lack of ground transportation.

In addition, the relationship between China and Africa has been developing for more than half a century, while economic ties between China and Latin America have only developed in the past two decades.

Therefore, while China’s Latin role is clearly on the rise – very visibly during Li Keqiang’s visit to the region last week – it is likely to remain relatively limited.

Takeaways

Read previous

Global Economy

The Modi Marathon

May 27, 2015