The Last Part of Sabria’s Journey

The last night of a long journey from Otilja, Syria to Dusseldorf, Germany for the world’s oldest refugee.

March 18, 2014

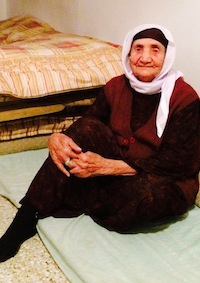

Sunday of the Crimean referendum. The Malaysian airplane still missing. In Athens, the Golden Dawn is leaking. Sabria Khalaf, 107, the world’s oldest refugee, is not preoccupied with any of that. Over her head, there is a full moon tonight. The last night of a long journey from Otilja to Dusseldorf.

On the way to the Athens apartment that shelters numerous Syrian refugees, a brief spell of camomile. The elderly cab-driver calls the area with its old name, Dourgouti, from the time that it used to be a shanty-town with tents and humble abodes housing refugees and exiles. Land remembers.

I enter half expecting last rites, something resembling a wake. (What else to expect when the other has seen more than a century?) The woman standing in the door-frame opens her arms. Her warm embrace is a tight grip, as she lays affirmatively three consecutive kisses onto my cheek.

“Where have you been?” Her mouth whispers wishes: “Live long, live well, be blessed and protected. Inshallah!”

Everything packed

An electric heater and a can of salt on the floor, beside her mattress. And the luggage. Everything packed, ready to go. Most of her belongings have already been sent to Germany with one of her sons.

She made sure to pack the white clothes from the Lalish pilgrimage, the journey that every Yazidi must do once in a lifetime. The rest – memories, stories, joys and sorrows – she left behind. Only sometimes at night, she dreams of Otilja, her home and her neighbors.

The table in her house in Otilja was always full of food for everyone. Not just the family. Everyone. She made the finest, most delicate kibbeh, stuffing inside onions, herbs, meat and spices.

She gave birth 17 times. And delivered countless as the village midwife. She was even called upon for help in the surrounding towns and villages, whenever a baby was due. With no medication, no hospital infrastructure, no other assistance than that of God Almighty.

She raises her arms once more, her flickering fingers unfold like a fan in the air. She puts them down again and pulls the creased skin around her silver ring.

A high price

Many died. Smallpox, disease, wars and massacres – “72 massacres for the Yazidi” in total – death took its toll.

But so did life. For every soul she brought to this earth – and they must have been hundreds, even thousands – Sabria may have accepted no pay, but must have received a small ransom. Put them altogether, one on top of the other, all 107 years of her existence registered in the spark of her lash-less eyes.

All of her family has resettled in Germany over the years, like many Yazidis. Except for her son Ali, who remained back to fetch her, and one daughter who stayed behind. Despite the happiness awaiting, the mind lapses back. She worries. War is still menacing. What can she do? What can we all do?

She is restless: full of plans, full of energy and full of hope. What lies ahead is not a farewell, but a feast. She talks more than everyone else, she wants to express her gratitude and thank every single person who helped her along the way.

She recounts the names. Even remembers the smuggler who carried her on his shoulder. They paid a high price, “though it was probably too high a price” she complains at once, resolutely tightening her lips.

“Until I have enough!”

The last part of the journey, is in a few hours. She will leave the compound apartment at 4:30 am and be escorted to the airport, alongside her son. Papers stamped with the oblique “Dublin II” sign. Morning flight to Dusseldorf.

“They will all be waiting for me. All my relatives. I told them not to come all the way to the airport. One is pregnant. No. They will all come. If you count them altogether, they exceed forty.

“I will be received as someone very important, as if I were a president! There will be flowers and embraces and tears and kisses and laughter and music and television and a lot of food for everyone. There will be joy!” She giggles.

“A long life is tiring. But tomorrow night, I will be a young girl again!” She jokes and makes everyone around her laugh. “I shall hold them tight, and kiss them and squeeze them and inhale their smell. For the whole day, and for another two or three years. Until I have enough!”

At times like this, one stops counting. After all, Sabria’s dear husband, Ibrahim, “lived until he was 103, and had all his teeth!” she says with pride. “And someone else in her family reached 135” adds her son.

Sabria is not traveling in order to die. She is traveling in order to live. Until she has had enough.

Post-Script

I heard of Sabria from Behzad Yaghmaian, the Iranian-born writer who initiated the campaign with The Globalist for her family reunification.

On a long walk through chilly Athens the night he met her, he spoke of her epic journey and her grandmotherly sweetness. His words touched people worldwide and with their active involvement, the last part of her journey became feasible. In a letter to his infant daughter Zoe, he writes about Sabria with tearful eyes. He hopes she remembers him.

“I love Behzad like my own children,” she says. “And I thank him. I thank everyone who has helped me along this journey. Inshallah!”

As for myself, I walked away having shed no tears. Her resilience already makes this world a better, brighter place. Or so it seems under night-skies of a hesitant but definite spring.

Editor’s note: Sabria Khalaf arrived safely in Germany on Monday, March 17, 2014.

Takeaways

Read previous

Shortsighted Russia, Patient China

March 18, 2014