Shanghai — Gazing At Its Own Image

The Potemkin Village that is Shanghai reflects China’s love of show.

December 25, 2014

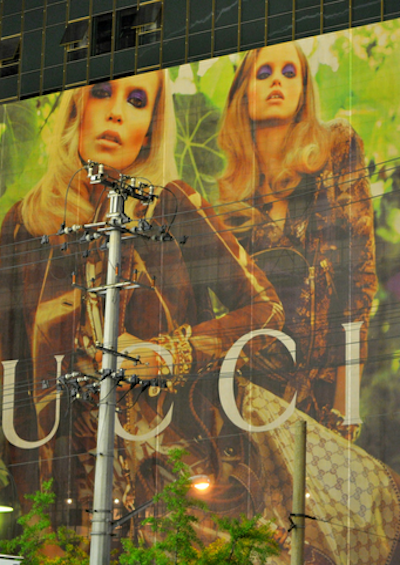

Shanghai is a city obsessed with its own image. This was especially apparent in the lead up to Expo, when giant billboards and video screens unabashedly declared Shanghai’s ambitions for growth. Here, hype forms an integral part of the landscape. Shanghai is often identified with its most stylish female inhabitants.

Shanghai: In-Depth Look at a Global City

▪ Shanghai – A City Hungry for the Future

▪ Shanghai – Gazing At Its Own Image

▪ Shanghai and China’s Embrace Creativity

▪ Shanghai’s Thames Town

▪ Shanghai: The Underground Economy

Living here, one gets the sense that the city itself takes great delight in gazing in the mirror, preening. Shops selling luxury brands are multiplying everywhere, despite the fact that few Shanghainese can afford them.

The malls that house these shops are so empty that locals call them ghost malls. The fact that their clientele is only virtual doesn’t seem to be a problem.

As China’s image of growth, Shanghai is pure window display. The city’s fascination with façade is frequently condemned. To critics, Shanghai’s embrace of urban spectacle is tied to a harmful neglect of the needs and desires of the real, living city.

There is no doubt that this destructive construction of spectacle is increasingly at work in Shanghai. Aligned with the all too common conception that the modern is necessarily Western, it manifests itself in intermittent campaigns to clean up the streets.

A Potemkin city of glamour and gloss

At their worst, these cleanup crusades accentuate a damaging lack of confidence, and seek to erase all signs of a local “backward” and “uncivilized” culture. Street food, hanging laundry and people in pajamas are all forcefully replaced with a tired, depressing view of Shanghai as a “Global City” that is filled with Gucci stores and KFCs.

Contemporary Shanghai’s most searing critic, MIT economist Yasheng Huang, shares this vision of a city that is cloaked in a deceptive layer of glamour and gloss. Mocking the veneration of “foreign observers” who are too easily duped, Huang accuses Shanghai of being “the world’s most successful Potemkin metropolis.”

The substance of Huang’s critique is an attack on what he calls the “Shanghai model of growth,” which came to the fore in the 1990s. According to Huang, the Shanghai model is based on a high-speed urbanism that favors massive state-owned enterprise and giant multinational corporations.

Its primary aim is the attraction of foreign direct investment (FDI) and its success is measured solely by rising GDP. He contrasts this economic model with a vibrant bottom-up sector of small, private entrepreneurs from the countryside, which dominated China’s initial wave of economic reform that took place throughout the 1980s.

China’s mass wave of urbanization

This more organic, rural entrepreneurship creates wealth for individuals, not just for the state. It is these small private businesses, Huang argues, rather than the state-led crony capitalists responsible for the spectacular rise of Shanghai, that are the real force behind China’s economic miracle.

Perhaps the separation between these “two Chinas” is not as neat as he suggests. China, after all, is currently in the grip of a mass wave of urbanization, the biggest the world has ever seen. The rural entrepreneurs that once revolutionized village life are now seeking their fortunes on the city streets.

Shanghai’s dynamic rise rests not only on the spectacular projects of a state-led urbanism, but also on the vibrancy of the life and culture of these migrant workers. Outside the hyper-modern gloss of new roads and skyscrapers, there is a thriving micro-commercial culture—made up primarily of migrants from the countryside — which constitutes a flourishing informal economy that infiltrates the urban core.

Moreover, as the “dragon-head” of the Yangtze River Delta, Shanghai is intimately connected with the entrepreneurship of the region of the country Huang celebrates most. What, after all, is the urban gloss of Shanghai, if not a shop window for the back-alley factories of Zhejiang?

It is possible to understand the divide between “two China’s” as an abstract distinction between two different economic orders that operate simultaneously in the city.

This formulation is derived from the historian Fernand Braudel, most famous for his monumental three-volume history of capitalism. The fundamental conclusion of this epic work is that there is a dialectic between capitalism on one hand, and its antithesis, the “non-capitalism” of the lower level on the other.

The love of a really good show

China loves a good show. It famously invented gunpowder, but rather than use it for deadly ammunition, it created grandiose firework displays.

This deep respect for pageantry is apparent in the Forbidden City, headquarters of China’s imperial power, whose intricate layering ensures that every visitor participates in an elaborate theatrical performance. The Chinese skill at staging such performances was revealed to the world in the astonishing opening ceremony of the 2008 Olympics.

A year later, the 2009 celebrations for the 60th anniversary of the Communist Party occurred under a sunny blue sky. This did not happen naturally. The party manipulated the weather for the event.

In China, it is no secret that these spectacles are choreographed. That the Olympic fireworks were “Photoshopped” for TV, that pretty smiling girls were brought in for the opening — or that the clouds were seeded for the Party’s grand parade — should come as no surprise.

In China, illusion has long functioned as a crucial currency of power. You only have to visit the Great Wall to realize that China’s greatest monument was built more as a symbol than for any functional purpose.

This profound attention to exteriority and façade attains an intensely personal expression in the Chinese concept of “face.”

To lose face, in this shame-based culture, is itself a devastating failure and thus functions, for both children and adults, as an enormously powerful mechanism for behavioral control. In China, people recognize that spectacle works.

Light and corruption

The Western philosophical tradition has a deep-rooted animosity to spectacle. China has an altogether different outlook on the spectacular. It does not condemn illusion. This acceptance of spectacle is rooted in a philosophical tradition that, unlike the West, does not associate brightness with truth and darkness with the falsity of illusion.

According to Chinese philosophy, yin and yang emerge together out of primordial emptiness. They are interconnected and give rise to each other. The world is produced through their constant rotation of shadow and light. Time itself is governed by this constant shifting change.

Liberals in China attack the lack of transparency as the dark side of China’s recent reforms. When a secret sub-sector of society has hidden access both to great power and to great wealth, the inevitable result is corruption.

The concealment of the party has created a mafia state run off crony capitalism.

Hope for the future rests on the forces of openness — globalization and cyberspace — that will eventually force light on this hidden realm. To these critics, there is something inherently dishonest, and morally suspect, in a city that so delights in pure show.

Editor’s note: The above text is adapted from “Shanghai Future, Modernity Remade,” by Anna Greenspan, London, C. Hurst & Company, 2014.

Takeaways

Shanghai is a city obsessed with its own image.

As China’s image of growth, Shanghai is pure window display.

China has a different outlook on the spectacular than the West. It does not condemn illusion.

China loves a show. It invented gunpowder, but rather than use it for ammunition, it created firework displays.

The Great Wall -- China’s greatest monument -- was built more for symbol than for function.

In China, to lose face is itself a devastating failure and functions as a powerful mechanism for behavioral control.

To Chinese liberals, there is something dishonest and morally suspect in a city that so delights in pure show