How to Combat Forced Marriage in Eurasia

Child marriages, early marriages and forced marriages are grave human rights violations. The practices have far-reaching and long-lasting consequences for individuals, families, communities and societies.

June 26, 2025

A Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) from the Global Ideas Center

You may quote from this text, provided you mention the name of the author and reference it as a new Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) published by the Global Ideas Center in Berlin on The Globalist.

Across Eurasia, gaps in legal protections and inadequate law enforcement are enabling child marriages, early marriages and forced marriages (CEFM) to persist.

Girls and young women from rural communities, low-income households, ethnic minorities and conflict-affected areas are especially at risk.

An archaic practice

The archaic practices expose girls and young women to a range of harms, including physical and sexual violence, health complications from early pregnancies — as well as exploitation.

Child marriage commonly disrupts the educational and economic prospects of young girls, curtailing opportunities to develop careers and economic independence. It traps many in dependency and intergenerational poverty.

The inherent power imbalance and lack of agency within such relationships leave child and forced brides vulnerable to coercion and abuse.

A grave human rights violation

The practice of child and forced marriages is a grave human rights violation. It has profound, far-reaching and long-lasting consequences for individuals, families, communities and societies as a whole.

While each Eurasian country has its own unique challenges shaped by unique cultural, economic and legal contexts, there are common underlying causes across the region.

Why it happens

The practice is underpinned by cultural acceptance, pressure to conform to traditional gender roles and deep-rooted patriarchal values associated with protecting family “honor.” Poverty also plays a significant role.

Families sometimes resort to child marriage to ease financial strain. Parents may also view marriage as a way to attain security for daughters or as a protective measure against sexual violence.

How to combat this scourge?

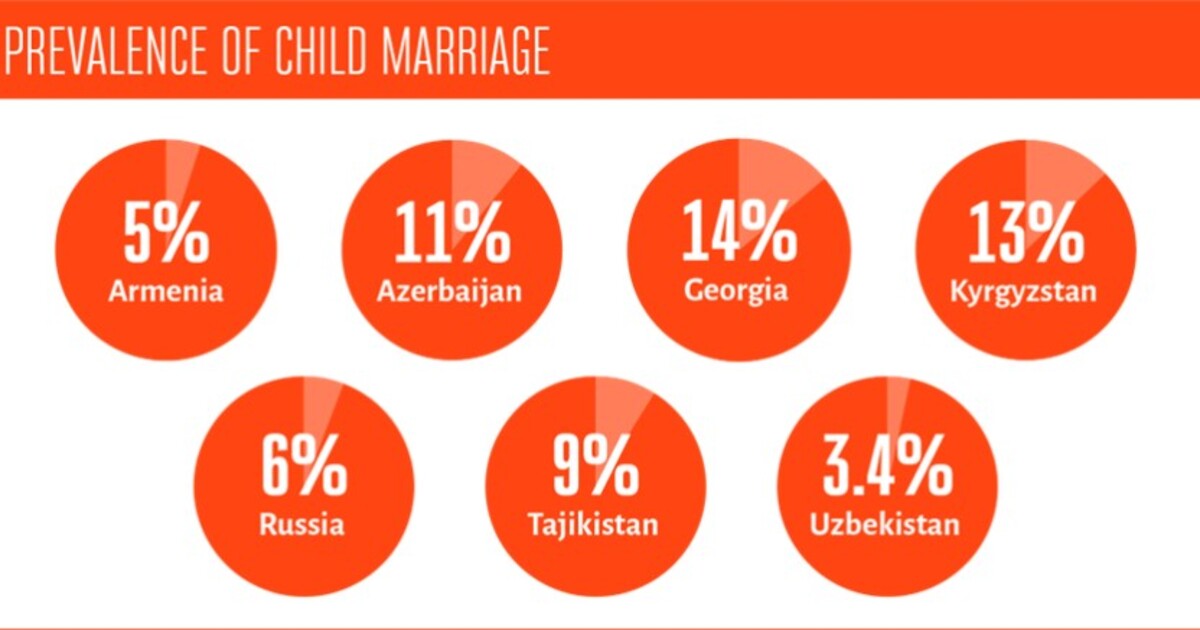

An analysis of relevant laws and their implementation in seven Eurasian countries — Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan — show that CEFM rates vary considerably between nations and minority groups.

To combat this scourge, governments urgently need to close legal loopholes, rigorously enforce laws, tackle the causes and improve support systems.

Variations within and between countries

Differences in cultural practices and attitudes influence the prevalence and acceptance of CEFM. In Georgia, for example, 14% of women aged 20–24 were married before the age of 18 — with rates rising to 25% in rural areas like Kvemo Kartli, compared to 8% in urban areas.

Uzbekistan has the lowest overall prevalence of child marriage at 3.4%, with the highest rate within the country rising to 11% in the eastern region.

However, under-reporting and limited awareness hinder accurate assessment of the prevalence of child marriage in the region.

Unsurprisingly, CEFM occurs more in certain marginalized ethnic minorities, where overlapping challenges include social exclusion, poverty, language barriers and isolation in remote localities. For some, child marriage is viewed as a way to protect community identity and honor.

Why Armenia is an inspiration

While every country examined has taken steps to address CEFM, the particularly interesting country case is Armenia. It ranks among the top 10 countries worldwide in terms of the rate of decline in the prevalence of child marriage since 2001.

As Armenian legal expert Naira Arakelyan explained, “An important factor is Armenia’s high regard for education, which has long been an integral part of Armenian identity and family expectations.”

Inconsistencies in tackling child, early and forced marriage

CEFM is not treated equally by criminal laws in the seven countries analyzed.

Kyrgyzstan criminalizes a broad range of offenses, including kidnapping for marriage, coercion into marriage or marital relations, violation of marriage age laws during religious ceremonies and bigamy or polygamy.

Armenia, Azerbaijan, the Russian Federation and Tajikistan envisage prosecution of abduction for forced marriage under general kidnapping laws. Meanwhile, Georgia prosecutes it under the crime of illegal deprivation of liberty.

However, all too often inadequate legal enforcement undermines progress and legislative loopholes permit perpetrators to go unpunished, even when criminal cases have been initiated.

Loopholes that allow the continuation of forced marriages

Legal protection gaps still exist that hinder access to justice for CEFM. For example, Azerbaijan and Russia exempt perpetrators from criminal liability for abduction if they voluntarily release their victims.

However, there is a real-life problem with that approach: If there is no other element of a crime, the fact of the matter is that refusing marriage after spending time, especially the night, in the house of an unknown man often elicits social stigma that forces young women to remain with perpetrators.

Comprehensive reform is urgently needed

Governments urgently need to improve protections against CEFM by closing legal gaps and strengthening governance and justice systems. To combat child marriage, the minimum age of marriage must be set at 18, with no exceptions (so far, only Azerbaijan and Georgia have done so out of the countries).

In addition, administering legal penalties is key to holding perpetrators accountable and also acts as a deterrent.

Another important step is that laws should be uniform across legal domains — constitutional, civil, family and customary.

States also need effective mechanisms to deliver consistent legal compliance and implementation at all levels of government — including local enforcement. Kyrgyzstan, for example, has a dedicated national policy and action plan to address CEFM.

Conclusion

Empowering young people is pivotal and warrants targeted investment to equip adolescents with the education, skills and resources to pursue alternatives to marriage. Financial incentives can be particularly effective in keeping girls in school.

Civil society has a critical role to play in providing services, advocating for women and girls and acting as a bridge between communities and policymakers.

Governments, for their part, should foster an enabling environment for civil society organizations by supporting their initiatives. This crucially includes ensuring freedom of operation and facilitating collaboration between stakeholders to empower broad-ranging action in order to root out CEFM throughout Eurasia.

Takeaways

Child marriages, early marriages and forced marriages are grave human rights violations. The practices have far-reaching and long-lasting consequences for individuals, families, communities and societies.

The archaic practice of child marriage exposes girls and young women to a range of harms, including physical and sexual violence, health complications from early pregnancies as well as exploitation.

Child marriage commonly disrupts the educational and economic prospects of young girls, curtailing opportunities to develop careers and economic independence. It traps many in dependency and inter-generational poverty.

To combat the scourge of CEFM, governments urgently need to close legal loopholes, rigorously enforce laws, tackle the causes and improve support systems.

To combat child marriage, the minimum age of marriage must be set at 18, with no exceptions.

A Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) from the Global Ideas Center

You may quote from this text, provided you mention the name of the author and reference it as a new Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) published by the Global Ideas Center in Berlin on The Globalist.