From Anti-Russian McCarthyism to Pro-Russian Trumpism

Trump uses his coziness with Putin and Russia as a weapon against domestic liberal enemies, rather than as a coherent peace strategy.

February 18, 2026

A Global Ideas Center, Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) from the Global Ideas Center

You may quote from this text, provided you mention the name of the author and reference it as a new Global Ideas Center, Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) published by the Global Ideas Center in Berlin on The Globalist.

Back in the 1950s, the United States, even a whisper of sympathy for Russia or the Soviet Union was unthinkable and seen as almost traitorous. The eventual rise of McCarthyism was all about rooting out what were presumed to be “un-American activities”, i.e., anything that could be perceived as socialist or communist.

A curious reversal of the 1950s McCarthy spirit

When we look at the global landscape today, it is much more nuanced. Inside the United States, however, especially at the top echelons of the Trump administration, there is almost a reversal of the 1950s McCarthy spirit.

Instead of assuming that every activity critical of the U.S. government is favoring communism, it is the government itself that has given up even the most basic forms of prudence when it comes to Russia.

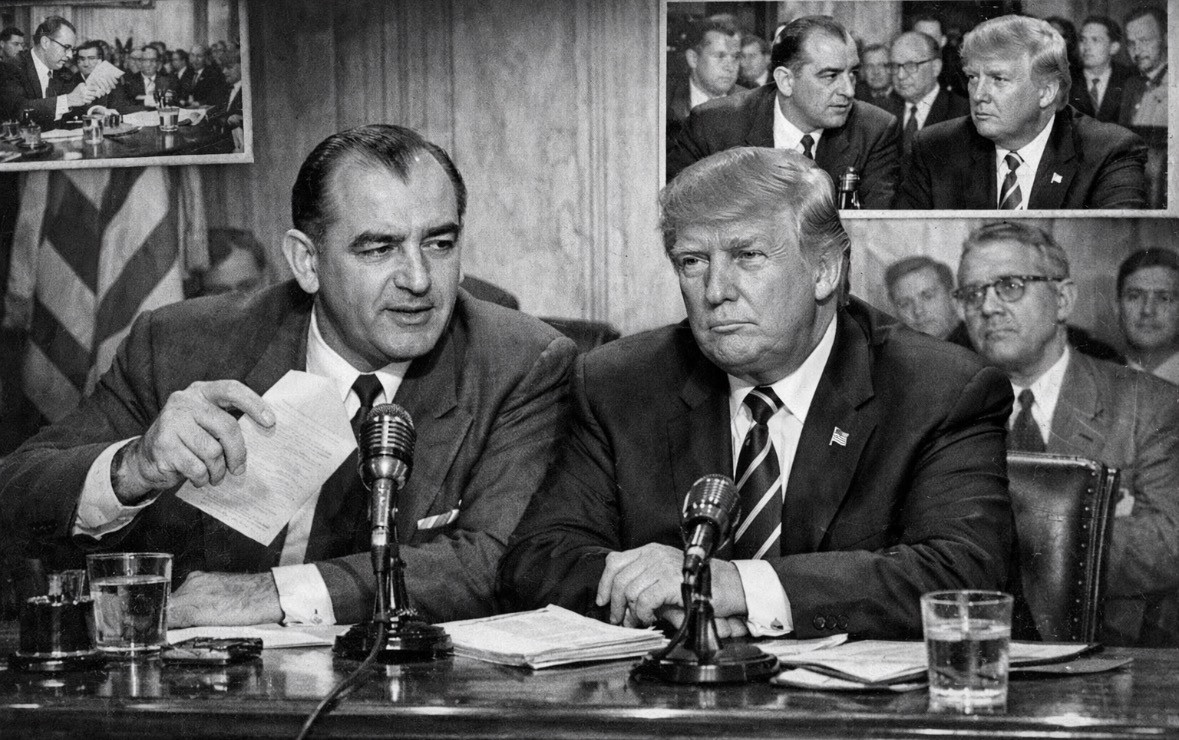

From the 1950s American demagogue to the 2020 edition

The irony – if not the tragedy – in the age of Trump is that a system built on checks, balances and pluralism has once again succumbed to a single demagogue.

In contrast to McCarthy, Trump has moved the United States in the opposite political direction. He favors Russia in every conceivable way and is deliberately and completely disarming the well-resourced U.S. government apparatus to monitor even clearly illicit activities on U.S. soil itself.

Then as now, this reflects structural vulnerabilities in U.S. political culture. This includes:

– the intense personalization of politics, especially the presidency

– weak party gatekeeping of Republican members of Congress

– a recurring appetite for crusades against “internal enemies,” aka the Democrats

– the use of foreign policy as a stage for domestic symbolic battles.

What McCarthyism actually was

It is important to note that what the phenomenon called “McCarthyism” rested on a broad, bipartisan domestic anti‑communist consensus that long predated Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI) and extended far beyond him.

Then-President Truman’s doctrine explicitly framed U.S. foreign policy around resisting Soviet expansion. That approach to foreign policy fed back into a domestic security state in which communism became a master threat linking espionage, subversion and ideological dissent.

McCarthy’s innovation

McCarthy’s innovation was to turn that consensus into a personalized, media-driven movement that targeted not only Soviet agents. He also applied it to liberal internationalists, State Department professionals, intellectuals and artists and cast all of them as quasi-traitors.

The senator thus fused foreign policy fear (of Soviet expansion, “losing China,” the division of Korea) with a populist story. In his eyes, a weak, multicultural elite had betrayed the “real America.”

Five examples

In this way, McCarthy tied anti-communism to ideas of race and national identity, even without openly talking about race. The following five examples, among many others, offer a window into how the anti-communist McCarthyism fervor swept the nation.

1. Alger Hiss was a State Department official accused by journalist and former communist Whittaker Chambers of belonging to a Communist cell. Convicted of perjury in 1950 for denying he passed documents to the Soviets, he was sentenced to five years in prison. The case became a defining symbol of McCarthyism.

2. Owen Lattimore was an Asia scholar accused by McCarthy of being “the top espionage agent in the United States.” Indicted for perjury, a federal judge dismissed the charges in 1955. Lattimore was professionally sidelined for five years.

3. Pete Seeger, a folk singer called before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1955, refused on principle to answer questions about his political beliefs. He was convicted of contempt of Congress and sentenced to a year in prison; his conviction was overturned on appeal in 1962. Still, he was blacklisted from network television for over a decade.

4. John Stewart Service, a Career Foreign Service officer and China expert, was accused by McCarthy of being a Communist sympathizer and fired from the State Department in 1951 despite being cleared by loyalty investigations six times. Although the Supreme Court overturned his firing in 1957 and he returned to work, his career never recovered.

5. Klaus Fuchs, a German-born physicist, confessed in February 1950 to passing classified atomic weapons data from the Manhattan Project to Soviet intelligence. His confession triggered the chain of arrests leading to the Rosenbergs.

The breadth of the FBI’s Cold War mandate

Together, these cases illustrate the breadth of the FBI’s Cold War mandate. It ranged from cracking Soviet codes and prosecuting atomic spies to running covert domestic disruption programs—all driven by the conviction that Soviet infiltration posed an existential threat to the American republic.

How Trump dismantled the monitoring of Russia’s anti-American activities

The flip side of this pattern is Trump’s position and actions regarding today’s Russia and Putin. The following five examples are strikingly consistent: the very agencies, task forces, interagency mechanisms and individual experts that the U.S. built after 2016 specifically to monitor and counter Russian hostile activity have been disbanded, defunded, or purged.

1. Attorney General Pam Bondi dissolved the FBI’s Foreign Influence Task Force, which had led post-2016 election interference investigations, citing resource reallocation and “weaponization” concerns, prompting warnings that it would deter future FBI probes of Russian interference.

2. The NSC halted key interagency coordination against Russian sabotage and cyberattacks, paused regular consultations with European partners, and the DOJ ended an oligarch-asset task force, as the administration sought warmer ties with Moscow.

3. Defense Secretary Hegseth ordered U.S. Cyber Command to pause offensive cyber and information operations against Russia, disrupting capabilities previously used to target Russian troll farms ahead of the 2024 election.

4. Trump fired the NSA and Cyber Command chief, Gen. Timothy Haugh, and his deputy; DNI Gabbard then revoked clearances for Russia-focused experts and sought to shrink the Foreign Malign Influence Center and ODNI staff.

5. The administration proposed deep cuts to CISA and ODNI, forced out about a third of CISA staff, sidelined election security teams, and reduced support for state and local cyber defenses, thereby increasing assessed national cyber risk.

No one put it better than Representative Jim Himes, the ranking Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee, stating: “Vladimir Putin is sneering with satisfaction as Donald Trump, aided and abetted by his director of national intelligence, guts the intelligence community in pursuit of his political vendettas.”

Four structural parallels between McCarthy and Trump

Analysts increasingly treat McCarthy less as an isolated aberration than as an early template for later demagogic politics, including Trump’s. The parallels that historians and commentators emphasize include:

1. Branding and spectacle

Both McCarthy and Trump turned their names into political brands, prioritized permanent conflict and relied on media drama rather than institutional accomplishment.

2. Conspiratorial politics

Each organized politics around vast, hidden conspiracies — communists in McCarthy’s case, “deep state,” immigrants, and “globalists” in Trump’s—whose exposure justified extraordinary measures and rule-breaking.

3. Elite‑bashing populism

Both attacked foreign policy and national security elites as weak or treacherous while simultaneously needing those establishments’ cooperation and resources.

4. Lack of governing strategy

Neither developed a coherent long-term policy project; power itself and the performance of combat against enemies became the organizing principle.

One concrete personal link is Roy Cohn, McCarthy’s staff counsel turned New York fixer, who played a key role in McCarthy’s aggressive tactics, particularly in targeting alleged communists.

Cohn later mentored Trump, whose combative legal and public relations strategies, aggressive attacks on investigators and refusal to admit wrongdoing helped transmit a political style from the Red Scare era into Trump’s late-20th-century business and ultimately his presidency.

From anti-Russian McCarthyism to “pro-Russian” Trumpism

The Cold War anti‑communism that McCarthy exploited defined the Soviet Union as the central external enemy, allowing almost any foreign or domestic contest to be framed as part of an existential struggle.

That framing justified a vast national security apparatus. It repeatedly subordinated democratic principles, sidelining the natural desire for fairness and equality—labor movements, civil rights, decolonization, and solidarity—to the imperative to present a united front against Moscow.

Trump sees Russia no longer an existential enemy

Trumpism appears to flip this by treating Russia not as the existential enemy but as a potential partner—or at least a regime whose interests are negotiable and whose authoritarian model is not morally disqualifying—while casting domestic opponents and U.S. allies as the more immediate foes.

Yet that transposition is less about a principled pro-Russian ideology than about logic, attitude and aspirations. This shift has occurred in three different areas.

1. Anti‑liberalism at home

Trump’s admiration for strongmen and hostility to liberal‑internationalist elites make moving along with Moscow, or making concessions in places like Ukraine, a way to repudiate the post-1945 bipartisan consensus, not simply to realign geopolitics.

2. Transactional nationalism

Proposals to recognize Russian control over Crimea and other occupied territories, to weaken sanctions, and to establish US–Russian working groups are framed as deal-making that serves American “interests” even when critics see them as pro-Russian.

3.Reassignment of treason

Where McCarthy targeted alleged pro‑Soviet sympathizers inside the state, Trump’s rhetoric frequently defines pro-sanctions, pro-NATO, or pro-Ukraine officials and allies as the real problem, accusing them of dragging the U.S. into wars or constraining presidential prerogatives.

Thus, what started as a reaction against McCarthy-era anti-Russian paranoia by being more open to working with Moscow has now become its own ideological project in which friendliness toward an authoritarian Russia functions as a weapon against domestic liberal and multilateralist traditions, rather than as a coherent peace strategy.

Why can one man grip a system built for pluralism?

The fact that both McCarthy and Trump could exercise outsized influence reflects recurring features of American political culture and institutional design rather than purely the charisma or pathology of individual leaders. Key elements include:

1. Crisis-driven politics

Periods of perceived national vulnerability—the early Cold War, terrorism and deindustrialization, financial crises, geopolitical retrenchment—create demand for simple explanations and aggressive leaders who promise to purge enemies.

2. Weak party oversight

U.S. parties lack strong hierarchical control. In both eras, ambitious outsiders could leverage media notoriety and grassroots anger to secure central positions, while party elites were slow to resist, fearing the loss of their positions.

3. Media tactics

While McCarthy exploited early television and sensational hearings, Trump leveraged cable news and social media to dominate the information ecosystem, turning politics into a permanent spectacle that rewarded transgression.

4. Leader personalized nationalism

The presidency’s symbolic role and long tradition of personifying the nation make it easier for large segments of the public to meld loyalty to the country with loyalty to a leader, even when that leader attacks institutions and allies.

While this does not apply to McCarthy, it is undoubtedly applicable to Trump, who is attacking institutions with near impunity against all norms.

In that sense, McCarthyism and Trumpism reveal how much the much-hyped American system of checks and balances depends on unwritten norms and elite self-restraint.

When those erode, the constitutional architecture alone does not prevent concentrated, personalized power.

The deeper political‑cultural story

Both eras use external conflict to manage internal fractures over race, status and the meaning of “real America.” During the Cold War, anti‑communism helped police the boundaries of whiteness, gender, sexuality, and loyalty, marginalizing dissident intellectuals, racial justice movements, and leftist immigrant traditions while presenting the U.S. as the bastion of freedom against Moscow.

In the Trump era, selective rapprochement with Russia coexists with aggressive confrontation elsewhere (e.g., Iran, China, Venezuela). Both approaches serve a narrative that divides the world—and the domestic arena—into sovereign, “strong” nations and allegedly decadent, globalist or “woke” enemies.

That narrative resonates with a long-standing sense of relative decline, institutional stagnation and loss of moral authority. Trump’s disruption of the old anti-Russian consensus serves to dramatize a break with an order many supporters view as having failed them.

Russia as a tool in the domestic struggle against domestic liberalism

Seen this way, the arc from anti‑Russian McCarthyism to pro‑Russian Trumpism is less a 180‑degree turn and more a cyclical repurposing of the Russian “other”.

This occurred first as the indispensable external threat that underwrote an expansive liberal empire, then as a counter‑liberal pole that a significant part of the American right can admire, excuse or instrumentalize in its struggle against domestic liberalism and multilateralism.

Whether this cycle ends in tragedy depends on whether institutions and political culture can recreate forms of pluralist self-government that do not require periodic, leader-centered crusades to stabilize themselves.

Conclusion

The odds are that this cycle of Trumpism will end in a tragedy, unless the public wakes up to the perilous danger that Trump poses if he is allowed to pursue his current destructive policy for the next three years.

Takeaways

In a complete reversal of many decades of U.S. policy, the Trump administration has given up on even the most basic forms of prudence when it comes to Russia.

Trump favors Russia in every conceivable way and is disarming the well-resourced U.S. government apparatus to monitor even clearly illicit activities on U.S. soil itself.

McCarthy’s innovation to target not only Soviet agents, but also liberal internationalists, State Department professionals, intellectuals and artists.

Putin couldn’t be happier that Donald Trump, aided and abetted by his director of national intelligence, guts the U.S. intelligence community in pursuit of his personal political vendettas.

Trump’s coziness with an authoritarian Russia functions as a weapon against domestic liberal and multilateralist traditions, rather than as a coherent peace strategy.

McCarthyism and Trumpism reveal how much the much-hyped American system of checks and balances depends on unwritten norms and elite self-restraint.

In the Trump era, selective rapprochement with Russia coexists with aggressive confrontation elsewhere (e.g., Iran, China, Venezuela).

A Global Ideas Center, Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) from the Global Ideas Center

You may quote from this text, provided you mention the name of the author and reference it as a new Global Ideas Center, Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) published by the Global Ideas Center in Berlin on The Globalist.