Sheinbaum’s Formula: Technocracy, Populism and Female Power in Latin America

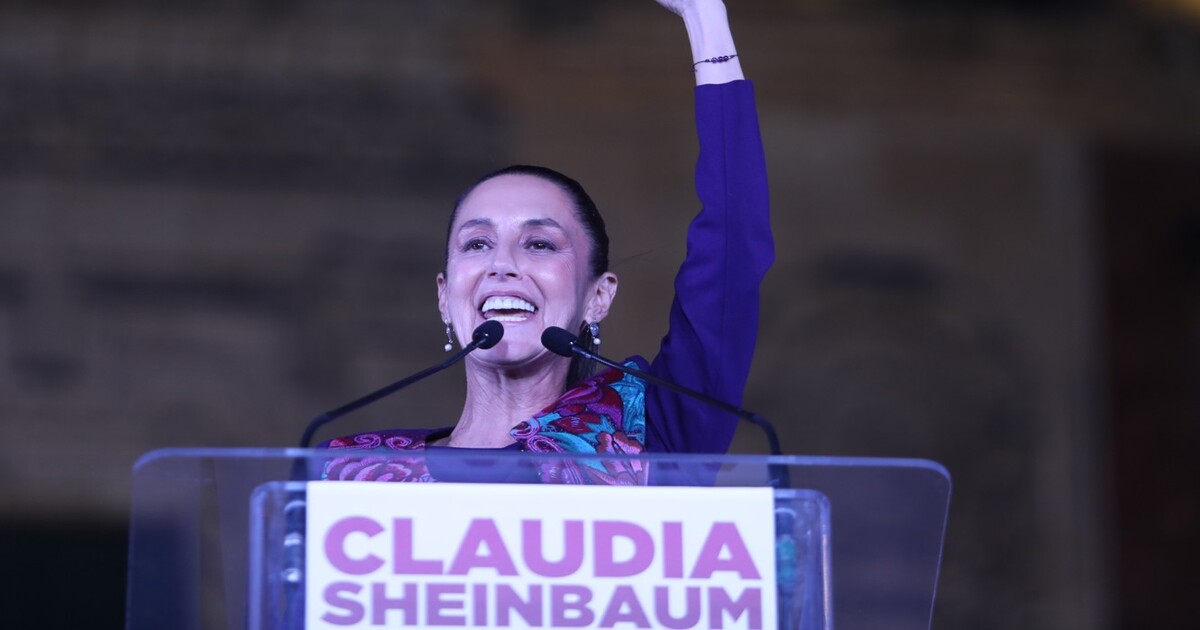

Claudia Sheinbaum’s 2024 election signals a new wave in Latin America’s “Pink Tide” of female presidents. But she needs to learn from other women in other Latin American countries who governed before her.

June 7, 2025

A Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) from the Global Ideas Center

You may quote from this text, provided you mention the name of the author and reference it as a new Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) published by the Global Ideas Center in Berlin on The Globalist.

Claudia Sheinbaum became Mexico’s first female president with a technocrat’s resume and a populist party behind her. A protégé of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), she retained his slogan “for the good of all, the poor first,” while promising to “follow the data.”

Sheinbaum’s 2025 “Plan México” — 13 goals across industry, security, welfare and environment — reads more like an engineer’s blueprint than a politician’s manifesto.

Yet, the grandiosity of targets has already revealed gaps. Dozens of ministries and advisory councils churn out indicators, but few dashboards show genuine progress.

Just another political playbook?

The risk is that Plan México becomes another political playbook — full of charts but short on deliverables — a fate shared by Brazil’s former president Dilma Rousseff’s economic blueprints and Argentina’s former president Cristina Kirchner’s social-spending drives.

In contrast, former Chilean president Michelle Bachelet and former Costa Rican president Laura Chinchilla combined technocratic planning with disciplined communication: They set realistic milestones and iterated when things went awry. Sheinbaum, in comparison, has offered few course corrections.

Her reliance on technical teams has insulated her from political feedback, even as popular support edges downward in polls. A “quiet manager” image may comfort investors, but it risks stagnation if policies lack real-world traction.

The legacy of technocratic women

Sheinbaum’s data-first style owes more to Bachelet than to the bombast of Cristina Kirchner or Honduran president Xiomara Castro. Bachelet, trained as a doctor, built consensus through expert panels — delivering pension reform and school improvements incrementally.

Sheinbaum echoed this in her early months — rolling out educational grants and climate programs without fanfare.

Yet Bachelet also navigated crises by owning mistakes. When pension reform stalled, she publicly revised her plan.

Doubling down

Sheinbaum has shown little appetite for admitting missteps. After environmental protests over a contested highway in Xochimilco, her team doubled down on engineering fixes rather than rethinking the project’s very premise.

That rigidity contrasts sharply with the adaptive leadership once displayed by former Nicaraguan president Violeta Chamorro. She rescued Nicaragua’s post-war economy by reversing controversial policies. Similarly, Costa Rica’s Chinchilla quietly shelved unpopular security measures when they provoked public backlash.

A technocratic veneer cannot substitute for political agility. Early evidence suggests Sheinbaum’s promise of data-driven innovation may mask an unwillingness to pivot — threatening to transform “technocracy” into technocratic inertia.

Populist divergences

Sheinbaum’s cautious planning also diverges from the visionary zeal of Rousseff or Kirchner. Rousseff’s reactionary fiscal stimulus in the face of consumer protests was clumsy but responsive.

Kirchner’s combative populism, though polarizing, rallied broad public movements. Sheinbaum, by contrast, treads a middle path: Neither fiery enough to galvanize nor flexible enough to recalibrate when policies underperform.

Her 2025 security figures — 20,000 arrests and plunging homicide statistics — have been touted as victories. However, they mask a surge in homicides coded as “undetermined intent,” suggesting the government is playing statistical games.

This recalls Rousseff blaming data quirks for Brazil’s crime spikes, as well as Kirchner-directed statistics offices accused of downplaying Argentina’s violence. A true technocrat would prioritize transparent methodology over headline grabs.

Four-pillar strategy

Sheinbaum’s four-pillar security plan — root causes, National Guard, intelligence and coordination — reads well on paper. Even so, poverty and youth unemployment — the plan’s social-prevention bedrock — remain stubbornly high. She has cut red tape for youth training programs, but schools report backlogs and understaffing.

Deploying Mexico’s National Guard and praising the military may mollify security hardliners, but it risks reviving fears of militarization — a legacy many Latin Americans reject after decades of dictatorship.

Bachelet’s civilian-policing reforms and Chinchilla’s community programs emphasized human-rights safeguards. Sheinbaum’s plans lack comparable guardrails.

Evolving policing culture

Her push for virtual-reality training and data-analytic crime maps suggests modernization. Yet veteran officers complain of hollow training sessions and a deficit of basic resources — patrol cars, radios and even uniforms.

This mismatch between high-tech ambition and low-tech reality echoes Kirchner’s pricey fleet of presidential planes amid budget cuts for provincial police and Castro’s troop deployments that left prisons in Honduras overcrowded and underfunded.

Real reform, as seen in Chile under Bachelet and Costa Rica under Chinchilla, requires building trust between police and communities. Sheinbaum’s approach so far emphasizes top-down enforcement over grassroots engagement — an omission likely to undermine long-term gains.

Fiscal discipline and social priorities

Sheinbaum’s first budget cut spending by 1.9% in real terms and aimed to shrink the deficit to under 4% of GDP. She simultaneously redirected funds to education, infrastructure and new social programs.

This mirrors Bachelet’s early balancing act but diverges from Kirchner’s run-away deficits and Rousseff’s mid-term austerity U-turn.

Her continued cash transfers and pension hikes have kept poverty rates stable but living standards barely budged. Surveys show Mexicans still cite cost of living and inequality as top concerns.

Plan México’s call for 25% investment-to-GDP and 1.5 million jobs hinges on private capital that remains cautious amid global volatility. Without assured financing, these promises risk becoming political manna rather than sustainable policy.

Plan México: Industrial roadmap

The roadmap to relaunch “Made in Mexico” — build industrial parks, upgrade seaports and halve firm-startup times — encapsulates her vision of state-guided development.

There is, however, the absence of clear revenue streams to support infrastructure bonds and public–private partnerships. Rousseff’s “Plano Brasil Maior” initially boosted manufacturing, only to founder amid budget shortfalls.

Sheinbaum’s avoidance of oil windfalls may guard against boom-bust cycles — but also leaves fewer cushions when crises hit.

Regional models and policy choices

Comparative examples underscore Sheinbaum’s tightrope. Nicaragua’s Chamorro tamed hyperinflation through orthodox austerity — Mexico’s fiscal stance is similarly cautious. Costa Rica leveraged tourism and tech hubs without heavy industry — Mexico’s plan mimics that, aiming to join global tech value chains.

Argentina’s Kirchner nationalizations remain a warning: Aggressive state control can stifle private investment. Honduras’s Castro faces skyrocketing deficits from populist wage increases — a trap Sheinbaum has so far sidestepped.

To succeed, Sheinbaum must tread between social-democratic generosity and fiscal responsibility, a challenge that has felled many predecessors.

Renewable ambitions

Sheinbaum pledged 45% renewable electricity by 2030 and backed rooftop solar subsidies — a stark reversal of AMLO’s oil-centric policy. She launched a $20 million river-clean-up drive and scaled “Sembrando Vida” reforestation into Central America. Mexico revived water-management laws and private irrigation pacts — classic technocratic fixes.

Parallel with Rousseff’s hosting of COP21 amid surging Amazon deforestation, Sheinbaum still props up PEMEX and CFE, diluting her green credentials.

PEMEX and CFE are heavily reliant on fossil fuels, plagued by corruption and inefficiency and stand in direct opposition to Mexico’s climate goals.

Without deeper reforms — such as phasing out fossil-fuels subsidies or empowering independent regulators — her environmental leadership risks being symbolic rather than structural.

Regional green leaders

In that regard, Sheinbaum joins Bachelet, who created Chile’s environment ministry and exported solar power, and Chinchilla, who maintained Costa Rica’s carbon-neutral grid. Even Castro of Honduras declared zero deforestation by 2029 and deployed troops to protect forests.

Their success hinged on sustained budgets and enforcement. Mexico’s water projects must translate into cleaner rivers: Early reports show only modest improvements in water quality, while illegal logging persists.

A true test will be Mexico’s next national emissions audit. If pollution and deforestation metrics fail to improve, critics will brand her environmental agenda as window dressing — just as they did with Rousseff and Kirchner after initial green promises went unfulfilled.

Symbolic and legal reforms in gender policy

Sheinbaum’s feminist framing brought a new Ministry of Women, constitutional equal-pay guarantees and cabinet parity. She launched a national Women’s Bill of Rights and a “national care system” for childcare and eldercare. These advances echo Bachelet’s maternity-leave expansions and Chinchilla’s anti-violence laws.

However, feminist NGOs note that budget cuts have slashed shelters and legal-aid programs, undercutting these reforms. Kirchner’s landmark gender-identity law likewise coexisted with underfunded support services, and Rousseff’s “Maria da Penha Law” also suffered from lackluster implementation.

Sheinbaum must not only pass laws but also secure line-item funding and robust monitoring. Failure to do so will consign her gender agenda to mere symbolism.

Budget tensions and critiques

The incongruity between feminist ideals and fiscal belt-tightening has drawn sharp rebukes. Women’s organizations accuse her of tokenism: Lofty speeches with house-keeping budgets.

The true measure of Sheinbaum’s effectiveness will be trends in femicide rates and women’s labor-force participation. Thus far, neither has moved decisively in the right direction — a sobering reminder that programming and money must align.

Reengagement and feminist diplomacy

To be sure, Sheinbaum jolted Mexico’s foreign policy into life: G20 attendance, calls for redirecting military spending to reforestation and a “feminist foreign policy” doctrine. Her liberalizing foreign minister has reopened talks with the United States on migration and trade while wooing Chinese and EU investors.

Yet, these initiatives risk echoing Kirchner’s ideological blocs or Rousseff’s BRICS gambit, if not backed by concrete deals. Mexico’s technocratic posture — hosting climate forums, pledging humanitarian aid — must yield binding agreements, not just speeches.

The coming U.S.-Mexico migration accord and any new trade pacts will test whether her diplomacy is substantive or performative.

Multilateral leadership and climate advocacy

Sheinbaum follows Bachelet and Rousseff in seeking multilateral prominence — expected to send a large Mexican delegation to COP30 and G20.

But unlike Bachelet’s post-presidency roles at UN Women and the WHO, Sheinbaum’s global ambitions hinge on delivering results at home. Without domestic wins in security, environment and social equity, her international brand of “feminist technocracy” risks appearing hollow.

Sheinbaum’s first eighteen months illustrate both the promise and perils of a technocratic-populist hybrid. She has mobilized data, streamlined planning and advanced symbolic reforms.

However, persistent violence, budget shortfalls, environmental backtracking and underfunded women’s programs reveal the limits of blueprint governance.

Female leadership does not guarantee lasting change

Comparisons to Bachelet, Chinchilla, Chamorro, Rousseff, Kirchner and Castro show that female leadership does not guarantee lasting change — implementation and political agility matter most.

If a “Pink Tide 2.0” is to succeed, Sheinbaum must move beyond technocratic design to deliver tangible improvements: Sustained drops in crime, verifiable green metrics, real gains in gender equality and binding international agreements.

Otherwise, her presidency risks joining the cycle of unfulfilled promises that have long defined the region’s pendulum swings between hope and disappointment.

The limits of technocracy: When data masks inertia

Sheinbaum’s presidency has been heralded as a data-driven departure from traditional political rhetoric — an era of dashboards, metrics and evidence-based policy. Yet, the early signs suggest that technocracy, in isolation, offers no safeguard against poor governance.

Data, while essential for diagnosis and planning, does not inherently ensure responsiveness, equity or effectiveness. Numbers can be massaged, indicators selectively reported and performance cloaked in technical language that alienates the public and stifles accountability.

Without mechanisms for democratic feedback, inclusive deliberation and adaptive leadership, technocratic governance risks descending into inertia. It can prioritize optics over outcomes, producing plans that look flawless on paper but falter in practice.

Worse, it can shield leaders from criticism under the guise of neutrality, reducing politics to a managerial exercise devoid of moral and social imagination.

The belief that “following the data” will lead to just and effective governance overlooks the fact that data interpretation is always political. What is measured, how it is measured and what gets excluded are choices shaped by power and ideology.

Conclusion

In the end, metrics must be married with political courage, empathy and institutional reform.

Otherwise, as Sheinbaum’s early trajectory hints, the promise of a feminist, technocratic presidency may be reduced to statistical theater — precise, polished and profoundly disconnected from the messy realities it seeks to govern.

Takeaways

Claudia Sheinbaum’s presidency has been heralded as a data-driven departure from traditional political rhetoric — an era of dashboards, metrics and evidence-based policy.

“Plan México” — 13 goals across industry, security, welfare and environment — reads more like an engineer’s blueprint than a politician’s manifesto. Dozens of ministries and advisory councils churn out indicators, but few dashboards show genuine progress.

Claudia Sheinbaum’s first eighteen months illustrate both the promise and perils of a technocratic-populist hybrid. However, persistent violence, budget shortfalls, environmental backtracking and underfunded women’s programs reveal the limits of blueprint governance.

The early signs of Claudia Sheinbaum's presidency suggest that technocracy, in isolation, offers no safeguard against poor governance.

The promise of a feminist, technocratic presidency may be reduced to statistical theater — precise, polished and profoundly disconnected from the messy realities it seeks to govern.

Sheinbaum's presidency risks joining the cycle of unfulfilled promises that have long defined the region’s pendulum swings between hope and disappointment.

If a "Pink Tide 2.0" is to succeed, Sheinbaum must move beyond technocratic design to deliver tangible improvements: Sustained drops in crime, verifiable green metrics, real gains in gender equality and binding international agreements.

Without mechanisms for democratic feedback, inclusive deliberation and adaptive leadership, technocratic governance risks descending into inertia.

Female leadership does not guarantee lasting change — implementation and political agility matter most.

In contrast to Sheinbaum, former Chilean president Michelle Bachelet and former Costa Rican president Laura Chinchilla combined technocratic planning with disciplined communication. They set realistic milestones.

What distinguished Bachelet was that she also navigated crises by owning mistakes. When pension reform stalled, she publicly revised her plan. Sheinbaum has shown little appetite for admitting missteps.

Real reform, as seen in Chile under Bachelet and Costa Rica under Chinchilla, requires building trust between police and communities. Sheinbaum’s approach so far emphasizes top-down enforcement.

A Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) from the Global Ideas Center

You may quote from this text, provided you mention the name of the author and reference it as a new Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) published by the Global Ideas Center in Berlin on The Globalist.