Yes to Russia Reparation Bonds for Ukraine

Unless oil prices unexpectedly surge bringing more revenues into the Kremlin’s coffers,, Putin will hardly be able to afford his war of annihilation against Ukraine for another two years.

October 29, 2025

A Strategic Assessment Memo (SAM) from the Global Ideas Center

You may quote from this text, provided you mention the name of the author and reference it as a new Strategic Assessment Memo (SAM) published by the Global Ideas Center in Berlin on The Globalist.

Russia is on the brink of recession. Unless an unexpected surge in oil prices brings more revenues into the Kremlin’s coffers, Putin will hardly be able to afford his costly war of annihilation against Ukraine for another two years.

If Europe and the United States support Kiev long and strongly enough, Putin will probably have to give in eventually and agree to a ceasefire along the front line.

Can Ukraine hold out?

In order for Ukraine to hold out long enough, it needs a lot of money and the confidence that its struggle is not in vain. That is why Europe should quickly provide it with much more money.

These funds must be sufficient to finance the defensive struggle for at least two years. This would also be a sign of hope for the people of Ukraine and a signal to Putin that Europe has staying power.

The ideal solution

The Russian central bank’s assets frozen in the EU would be ideal for this purpose. Rather late in the day, Europe is finally discussing concrete plans to use these funds for Ukraine to a much greater extent than before, namely as indirect collateral for an interest-free European loan to Kiev of €140 billion.

According to the proposal for a “reparation bond,” the Russian funds would be used if Moscow refuses to pay compensation to Ukraine after the war ends, which Kiev could otherwise use to repay the European loans.

Since Russia is unlikely to ever pay such reparations, this proposal amounts to not returning the assets to Moscow even after the end of the war, or even formally expropriating them in the end.

The hurdles

There are three serious objections to the idea of a reparations bond. First, expropriating the Russian central bank is not possible under international law. Ultimately, it is up to lawyers to assess whether state immunity under international law is so absolute that the victim of aggression has no chance of using the aggressor’s property for its own benefit or having it used for its own benefit.

The fact that it was possible to issue an international arrest warrant against Putin despite state immunity suggests that there may well be some leeway here.

Second, the European Central Bank in particular fears that resorting to Moscow’s assets could create a dangerous precedent, undermine confidence in the euro and jeopardize Europe’s financial stability.

However, Russia’s full-scale war of almost four years against a European neighbor is so unusual that potential planners of mischief could not really cite it in the future as a valid precedent that would allow them to confiscate European assets if they have a conflict with Europe.

Of course, it is possible that some rogue states may hesitate to invest funds in Europe or process payments through European institutions such as Euroclear in the future. But Europe froze Moscow’s assets almost four years ago. The interest income is already being paid out to Ukraine.

Conclusion

From an economic perspective, these interventions are already tantamount to partial expropriation. Measured against the exchange rate against the U.S. dollar and the Chinese renminbi, this has not harmed the euro. Nor has it posed a risk to financial stability.

On the contrary, the opposite is true. Europe can show here that it is capable of taking action. If it helps to put the aggressor in its place, this could strengthen rather than weaken the international reputation of Europe and the euro.

Takeaways

Unless an unexpected surge in oil prices brings more revenues into the Kremlin's coffers, Putin will hardly be able to afford his costly war of annihilation against Ukraine for another two years.

In order for Ukraine to hold out long enough, it needs a lot of money and the confidence that its struggle is not in vain. That is why Europe should quickly provide it with much more money, prominently including Russian assets.

The European Central Bank’s fears that tapping into Moscow's assets could create a dangerous precedent, undermine confidence in the euro and jeopardize Europe's financial stability have not materialized.

A Strategic Assessment Memo (SAM) from the Global Ideas Center

You may quote from this text, provided you mention the name of the author and reference it as a new Strategic Assessment Memo (SAM) published by the Global Ideas Center in Berlin on The Globalist.

Read previous

Global Politics

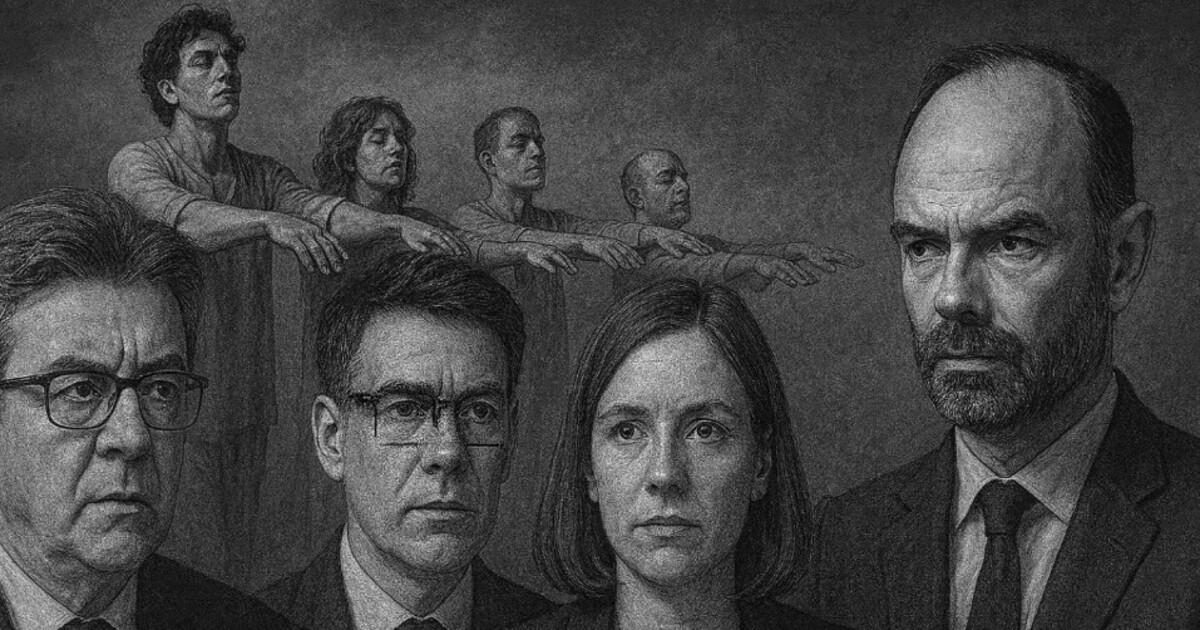

France’s Sleepwalkers

October 25, 2025