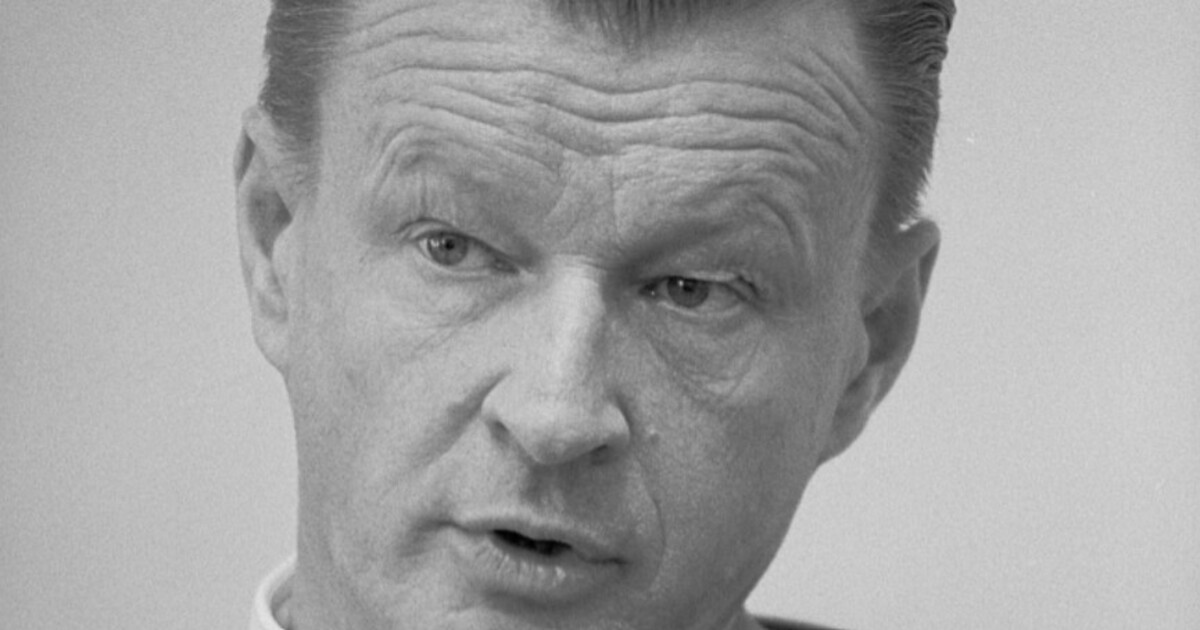

The Life of Zbigniew Brzezinski, America’s Cold War Prophet

Reflections on the former U.S. National Security Adviser and leading thinker on global affairs.

October 8, 2025

In his academic life and in government service, Zbigniew Brzezinski, the Polish-born former U.S. National Security Adviser during the Carter administration, always stood out as a strong advocate of U.S. power.

One of his key motivations in that regard was that the United States was the one nation on earth that had the capabilities of holding the Soviet Union in check. His own ambition was to provide strategic guidance to that effort.

Calling for “regime change” in the United States

However, after the early 2000s, during the George W. Bush administration, which saw a significant departure from his penchant for boosting U.S. power, Brzezinski was dismayed with what he considered a fundamentally wrong-headed approach to U.S. foreign policy.

To express his utter dismay with concepts such as conducting “wars of choice,” he began calling for “regime change” in the United States of America.

Adding a sideswipe on Europe

With his keen sense of analysis and search for balance, Brzezinski then added that Europe faced a problem, too. It did not even have any kind of coherent “regime” to overthrow.

Later, he also worried that Europe was turning into “a comfortable retirement home.”

The key reason, though, why Brzezinski was pessimistic that Europe could ever speak with one voice was Germany’s seemingly irrepressible penchant for east-facing mercantilism.

Can the Germans do proper math?

At a dinner with a senior executive of Siemens, the German engineering giant, Brzezinski got into an argument about the merits of German economic diplomacy. The Siemens executive said he had just been in Moscow, where the company had big investments.

Another dinner guest, Bob Zoellick, who had served in several Republican administrations and had played an important role during the negotiations to bring about German unification, interrupted.

What percentage of your global sales involves your deal with Russia, Zoellick asked. Two per cent, the executive replied. And what share comes from the United States, he asked. Twenty per cent.

“There was silence in the room,” Brzezinski told me later. “And of course everybody got the message. Your country had better learn how to calculate what your interests are.”

China and worrying about the “global Balkans”

Brzezinski also worried greatly about the rise of what he dubbed the “global Balkans.” His pessimism about the future of U.S. democracy meant that the country probably lacked the ability to confront a trend for global disorder.

After all, regardless of its faults, only the U.S. had the power and prestige to stop the world’s descent into a lethal era of great power conflict.

In Brzezinski’s eyes, the alternative to America was not China – but chaos. The reason why China could never emulate America’s universal appeal was simple: It was the opposite of an immigrant nation.

Nor could China replicate the network of alliances that the U.S. had built since the Second World War. To him, talk of China’s coming economic dominance was also overblown.

Brzezinski treated such forecasts with a similar disdain to predictions of Japan as the coming world superpower in the 1970s and 1980s.

America’s fear of terrorism

At the same time, Brzezinski worried about the U.S.’s fear of terrorism. To pinpoint its shallow, if not hollow form, Brzezinski described how he had often signed himself in as “Osama bin Laden” at the concierge of grand Washington buildings. He claimed that nobody caught him out.

In its more serious version, the widespread fear of terrorism made the country deeply susceptible to demagoguery.

To Brzezinski, this was a predictable offshoot of what he saw as the U.S. electorate’s shocking ignorance. “Americans don’t learn about the world, they don’t study world history, other than American history in a very one-sided fashion, and they don’t study geography,” Brzezinski lamented.

The big lesson to be learned

“If the U.S. doesn’t revitalize at home,” Brzezinski believed, “it will fail internationally. If it does, we may not necessarily fail internationally – but we will have to be intelligent to succeed. But if we continue to fail domestically, we will have no chance internationally, even if we do the right things.”

Postscript: A sentiment shared by Henry Kissinger

The professional rivalry between Zbigniew Brzezinski and Henry Kissinger, two East Coast Ivy League professors of international relations and former U.S. National Security Advisers, is the stuff of legend.

What is remarkable is how Kissinger, who outlived Brzezinski by three years, late in life described the similarities between the two men.

“As immigrants we knew about the fragility of societies and we had an instinct for the transitoriness of human perceptions,” Kissinger said.

“The question is whether Americans can ever understand that they are living in a continuous experience that has no end and that you can never segment life into different problems……Europeans knew that we were living in a continuous history. It never comes to an end.”

Kissinger’s personal appreciation of Brzezinski

Perhaps no one’s words of appreciation better and more cogently sum up the professional life of “Zbig” than Kissinger’s:

“Zbig had been one of the few who called us tirelessly to our duties far beyond the exigencies of the moment. He strove to provide structure to a world ever tempted by chaos and confusing mirages with vision. He was forever challenging his time with concepts of peace and freedom…”

These words weigh all the heavier as, by Kissinger’s own admission, the two men had “a relationship which, despite great mutual respect, was also shadowed by a certain competitiveness…”

Editor’s note: This feature is based on excerpts from “Zbig: The Life of Zbigniew Brzezinski, America’s Cold War Prophet” (Bloomsbury, 2025)

Takeaways

“Americans don’t learn about the world, they don’t study world history, other than American history in a very one-sided fashion, and they don’t study geography,” Brzezinski lamented.

“As immigrants we knew about the fragility of societies and we had an instinct for the transitoriness of human perceptions,” Kissinger said.

Zbigniew Brzezinski, the Polish-born former U.S. National Security Adviser during the Carter administration, always stood out as a strong advocate of U.S. power.

Brzezinski's primary motivation was that the United States was the one nation on earth that had the capabilities of holding the Soviet Union in check.

After the early 2000s, Brzezinski was dismayed with what he considered a fundamentally wrong-headed approach to U.S. foreign policy.

The key reason why Brzezinski was pessimistic that Europe could ever speak with one voice was Germany’s seemingly irrepressible penchant for east-facing mercantilism.

In Brzezinski’s eyes, the alternative to America was not China – but chaos. The reason why China could never emulate America’s universal appeal was simple: It was the opposite of an immigrant nation.