Dateline France: All of Gaul is (Still) Divided into Three Parts

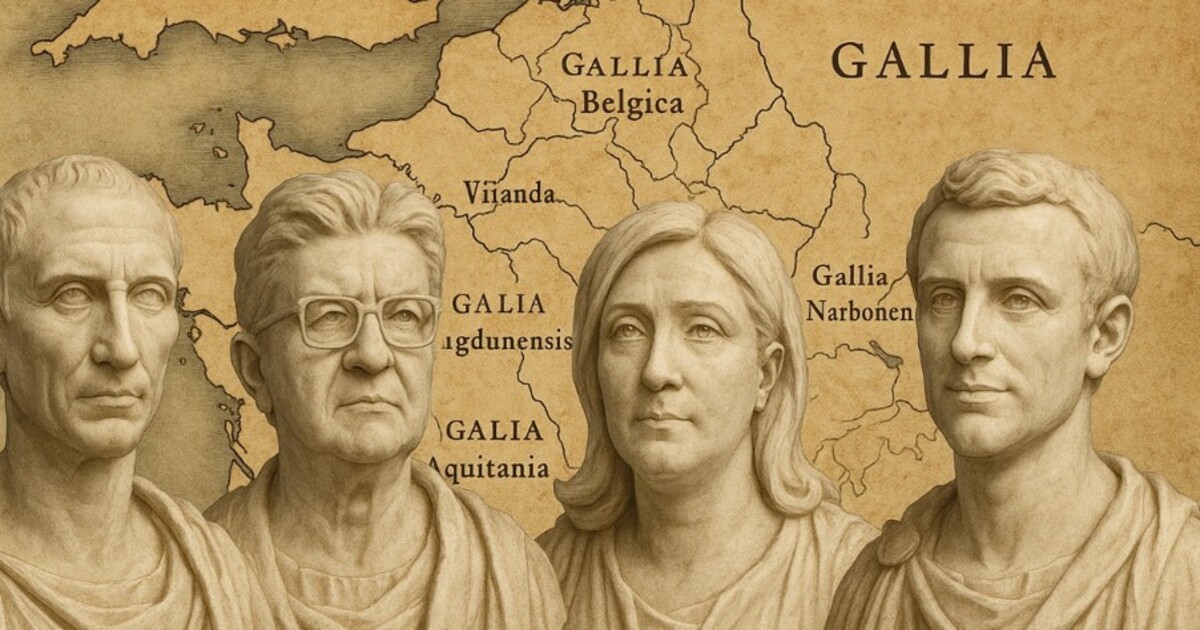

Caesar as a guide to understanding France’s political conundrum today.

October 17, 2025

A Strategic Assessment Memo (SAM) from the Global Ideas Center

You may quote from this text, provided you mention the name of the author and reference it as a new Strategic Assessment Memo (SAM) published by the Global Ideas Center in Berlin on The Globalist.

“All of Gaul is divided into three parts” — this is bound to be the most fitting description of the conundrum that contemporary French politicians find themselves in.

It has been offered by Denis MacShane, a Francophile and the former UK Minister for Europe under Tony Blair.

In looking at the political scene in Paris, he points to that famous opening line in the first volume of Caesar’s book “Commentarii de Bello Gallico” (Commentaries on the Gallic War), written in 58 BC.

Caesar as a visionary

Obviously, in Caesar’s day, Gaul was not divided into political groupings, but into three different population groups that inhabited the area — the Belgae, the Aquitani and the Celts (whom the Romans called Gauls).

The dividing lines back then were not political ideologies, but rivers — the Garonne, Marne and Seine. Caesar did note, however, that the three groups differed from one another in language, customs and laws.

Will tribal divisions once again lead to self-defeat?

In our time, the divergences among the three political blocks in France — the left (including the hard left), the center (which includes the Macron camp and the center right), as well as the hard right — seem insurmountable.

Just as in Caesar’s times, tribal divisions may lead to yet another self-imposed defeat of Gaul.

For most of France’s contemporary political tribes, especially those on the left and the hard right, the fixation on “my way or the highway” currently seems to be absolute.

Fraternité anyone?

Dealing with economic realities, such as a continuous series of high budget deficits, does not even seem to be an afterthought in the minds of those politicians.

They seem convinced that they can play “truth or dare” with the financial markets and that they will come out victorious.

For most of today’s key players in French politics, the overarching principle seems to be to insist on the singular relevance and legitimacy of their own political, economic and social preferences.

Compromises are viewed as poison — the absolute belief in one’s ability to achieve a total victory governs above all.

An absurdly naïve, at best childish view of politics

That absurdly naïve, at best childish view of the essence of politics is perhaps best explained as a curious reflection of the lingering consequences of the French having lived under an absolute monarchy.

The absurd hope today is that one political camp will be victorious, and all others will then acquiesce. Each camp plays along in this game, doing so in hopes of getting its chance to turn the tables and become the absolute ruler.

Macron as a piñata

This rather anti-democratic, quasi-regal perception of political rule also explains much of the facile attitude with which many French look at their current president, Emmanuel Macron.

Not that Macron is without fault. He has a certain regal bearing and can come across as aloof and very arrogant.

However, the way in which Macron is currently made out to be the sole source of France’s deepening political troubles is completely absurd.

Worse yet, in a direct reflection of an apparently irrepressible “revolutionary” impulse among the French people, there is a belief that, if one kills the king or emperor, all things will be good again after the killing.

In other words, a profoundly pre-democratic spirit still lingers in 21st century France.

Aren’t we still an Empire?

This is also borne out by the fact that the French political spectrum of today has not yet digested the fact that France is no longer an empire.

The various parties’ absolute insistence on their own partisan political dogma is nothing else than a modern variant of an imperial mindset.

Moreover, as at any minor court, for each party and its representatives, the only relevant validation of their own ambition, views and rule is sought from within one’s own court, i.e., the high-level party functionaries as well as from among the party members who are activists. It is as if they exist only in an echo chamber staffed with their own folks.

Turning travesty into tragedy

What turns this travesty into tragedy is when those various imperial-minded political apparatuses turn wholly ignorant of painful economic facts of life.

It does not even seem to make a difference if an outside “nuclear” force, i.e., the rating agencies, moves to downgrade French public debt.

It is of no concern to anyone in the country that Italy’s public debt, due to that country’s greater fiscal discipline, is now rated higher than France’s.

Rather than this being seen as a call to (common) action, the lustful insistence on the corrosive internal divisions that characterize French politics today makes the path to eventual compromise all the harder the longer it takes for reason and sensible compromise to prevail.

Above all other nations

Simply put, the body of French politics, with the exception of the center-right (which accepts the power of the bond markets not as a ruler over, but a very helpful reminder of reality and the socio-economic maneuvering space), evidently firmly believes that it stands way above all other European nations — indeed most nations on earth.

Most nations are realistic enough that they do not presume to stand above the laws of numbers and economics.

Other nations, such as Argentina, that have always tried to ignore those laws have basically lost a full century of economic potential.

What unites both the hard left and the hard right

Curiously, what unites both France’s left and its hard right, the Rassemblement National, is their insistence on reversing pension reform and busting the French budget with yet more social spending is nothing that markets will stand for.

That is a move that obviously runs completely counter to intergenerational fairness as well as to strengthening the French economy via more labor force participation.

No outside help in view

Meanwhile, the often-made assumption that the Germans can be called upon to stand for financing France’s rising public debt is fast becoming an ever less realistic assumption.

Germany’s economy, in its own way, is on a downward track and can therefore no longer be relied upon as a source of good credit back-up.

Takeaways

The way in which Macron is currently made out to be the sole source of France’s deepening political troubles is completely absurd.

A profoundly pre-democratic spirit still lingers in 21st century France.

Due to the irrepressible “revolutionary” impulse among the French people, there is a belief that, if one kills the king or emperor, all things will be good again after the killing.

The French political spectrum of today has not yet digested the fact that France is no longer an empire. The various parties’ absolute insistence on their own partisan political dogma is nothing else than a modern variant of an imperial mindset.

It does not seem to make a difference if an outside “nuclear” force, i.e., the rating agencies, moves to downgrade French public debt.

The body of French politics, with the exception of the center-right, evidently firmly believes that it stands way above all other European nations — indeed most nations on earth.

“All of Gaul is divided into three parts” — this is bound to be the most fitting description of the conundrum that contemporary French politicians find themselves in.

In Caesar’s day, Gaul was not divided into political groupings, but into three different population groups that inhabited the area — the Belgae, the Aquitani and the Celts (whom the Romans called Gauls).

In our time, the divergences among the three political blocks in France — the left (including the hard left), the center (which includes the Macron camp and the center right), as well as the hard right — seem insurmountable.

Just as in Caesar’s times, tribal divisions may lead to yet another self-imposed defeat of Gaul.

Compromises are viewed as poison — the absolute belief in one’s ability to achieve a total victory governs above all. This is best explained as a curious reflection of the lingering consequences of the French having lived under an absolute monarchy.

A Strategic Assessment Memo (SAM) from the Global Ideas Center

You may quote from this text, provided you mention the name of the author and reference it as a new Strategic Assessment Memo (SAM) published by the Global Ideas Center in Berlin on The Globalist.