Italy: The Taming of the Populists?

What are the challenges for Italy?

September 22, 2022

Italy remains the weakest link in the Eurozone chain. The OECD expects Italy’s working-age population to decline by 12.5% by 2040. If so, Italy’s economy can only grow if it makes much better use of its labour force.

The fact that Italian productivity has almost stagnated for 20 years, increasing by only 4% over that entire time period, presents a big problem.

In contrast, labor productivity in the Eurozone outside Italy rose by a cumulative 22% in the 20 years until the COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020.

Whether Italy’s public debt (likely 144% of GDP in 2022) is sustainable in the long run thus remains an open question.

Popular discontent

Unsurprisingly, the dearth of economic growth has fuelled discontent with the political elite. For almost 30 years, political newcomers have promised change, but without delivering on their promises.

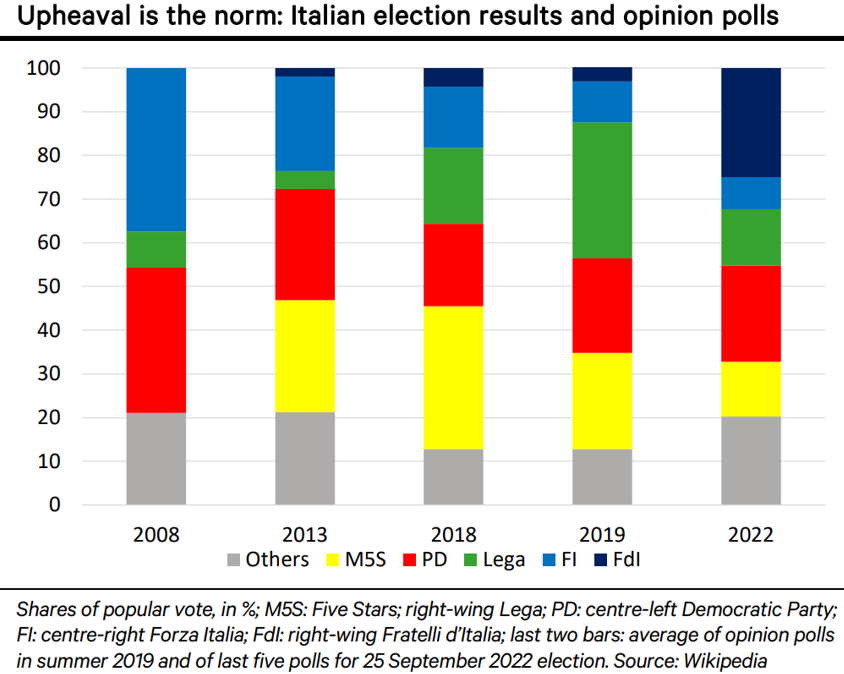

This process started with Silvio Berlusconi in the mid-1990s. In the past 10 years, various populists from the left and right have surged in the polls or even gained office, only to look much tamer and deflated a few years later.

The anti-establishment Five Star Movement, founded by the comedian Beppe Grillo, won the 2018 national election but has lost half its appeal since then.

Matteo Salvini from the right-wing Lega dominated the polls in 2019, only to see support for his party drop below 15% again.

Meloni’s turn?

The new upstart is Giorgia Meloni, the leader of the right-wing Fratelli d’Italia party, a party with some post-fascist roots.

Opinion polls project that her Fratelli (“Brothers” in Italian) party will garner about 25% of the popular vote in the September 25 election.

In an alliance with Salvini’s Lega and Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, Meloni looks set to win a majority of seats in both houses of the Italian parliament.

Short of a major election surprise or a hiccup in her somewhat fragile alliance, she will likely succeed Mario Draghi as prime minister shortly.

Heading for turmoil? Probably not

Some aspects of Meloni’s “Italy first” rhetoric resemble the mantra of Trump. Her disdain for the EU bureaucracy in Brussels contains echoes of the Brexiteer arguments in the UK.

Could her victory spark turmoil in the Italian bond market? Or even a new euro crisis, if investors worry that escalating conflicts between a Meloni government and the EU could put an Italexit risk on the table? In my view, that seems unlikely.

Taming the populists

The European Union certainly has its flaws. But it remains a great instrument to contain disagreements between sovereign nations.

EU leaders meet each other at least once a quarter on average. They often need each other to get things done in many fields. That exerts a useful discipline.

Italy arguably suffered its worst political accident already, in 2018, when the then-dominant populists from the right and left, Five Star and Lega, combined to form a government. However, despite a few domestic policy mistakes, they did not derail the EU train at all.

Likewise, Austria’s right-wing FPÖ party did not cause a stir in the EU either when it was part of a center-right government in Vienna from 2017 to 2019.

Meloni getting real

Sniffing power, Meloni has worked hard to be electable. She staunchly supports Ukraine. Her stance on migration and subsidies could conflict with EU rules.

Expect some noise. But far from toying with any Italexit idea, she now merely demands to renegotiate how Italy can spend its €192 billion share of the EU’s €750 billion NextGenerationEU program. That is par for the course.

The EU may be open to some changes as to how the money is used as long as Meloni implements the modest pro-growth reforms that the EU demands as a precondition.

An immediate debt crisis looks unlikely. However, it would take sustained and serious supply-side reforms beyond the progress made by Mario Draghi to dispel doubts about whether Italy’s debt is sustainable in the long run.

Takeaways

The dearth of economic growth in Italy has long fueled discontent with the political elite. It doesn't help that, for almost 30 years, political newcomers have promised change without delivering on their promises.

Various Italian populists from the left and right have surged in the polls or even gained office in the last 10 years – only to look much tamer and deflated a few years later.

The new Italian upstart is the leader of the right-wing Fratelli d’Italia party, Giorgia Meloni. She will likely succeed Mario Draghi as prime minister shortly.

Some aspects of Giorgia Meloni’s “Italy first” rhetoric resemble the mantra of Trump and her disdain for the EU bureaucracy in Brussels contains echoes of the Brexiteer arguments in the UK

Far from toying with any Italexit idea, Giorgia Meloni now merely demands to renegotiate how Italy can spend its €192 billion share of the EU’s €750 billion NextGenerationEU program.

Could Giorgia Meloni’s victory spark a new euro crisis if investors worry that escalating conflicts between her government and the EU could put an Italexit risk on the table?